|

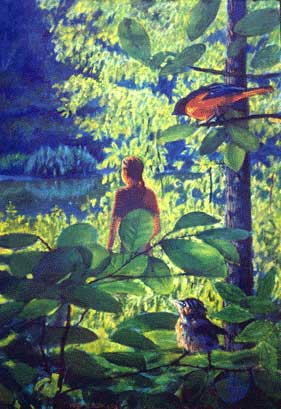

ORIOLES AND HERO'S WETLAND

Hero The Oriole

Ode To Orioles

(in two parts)

Part 1

About Hero the Oriole and How He Got his Name.

My wife and I found a small wetland

Of cattails and sycamores

some people called a "swamp"

and wondered why it was not drained.

We were walking on a little peninsula

that jutted out into the waterplants.

A bird was chattering above us, very upset.

I was watching a Red Headed Woodpecker

but the insistent chatter of the Oriole

caught my wifes attention.

Hero, his Dad, and my Spouse

I looked around, and as I did a baby Oriole leapt from

our path

right into the waterplants, hopping out a log into the pond.

His mother was chattering in protest because we were about

to stumble onto her baby.

She was right and her complaints were just.

The baby hopped off the log and fell into the water.

It was our fault, though we intended no harm.

The baby bird was in danger of drowning.

So I walked out the log, balancing myself with a staff

and perched the baby on small twig

and brought it back to the peninsula

and set it at the base of the birth-tree.

"What a hero he is" I said to my wife

and we backed away thirty feet, behind some bushes

and watched to see if the mother would feed it.

Right away she arrived with food for her wet baby.

She chattered and called to it sweetly,

encouraging it to climb upward.

Then we saw a blurr of tiny wings, and Hero’s brother

or sister

came fluttering down from the nest.

Two babies.

After watching the mother feed them both for awhile, we left----

sure that the little Hero and his sister or brother were safe.

And this is why I named this place Hero’s Wetland,

after a brave baby bird that fell into the water

but climbed up in a tree and survived.

Hero’s Wetland, would prove to be a hidden place full of

many unsung Heroes.

Hero

The next day I returned and found Hero

and his brother or sister and his parents gone.

I was surprised.

It raised the question of what happens to baby Orioles

When they leave the nest.

I wanted to know

and called various ornithologists. No one knew.

So a year passed, and I was ready the next year to find out.

Hero’s parents returned to the same peninsula.

They nested in the tree next to the tree of the previous year.

I waited the few weeks until the babies showed signs

they would come out of the nest.

There were three this time, and each one fluttered down

in a blurr of wings, just like last year. Over succeeding years

I ended up calling this time

the time of the Rain of Orioles---

since all over the wetland, the many Orioles nests give up their babies

and over the course of a few days Orioles rain down from the trees

here and there, in a fluttering of tiny silver wings.

So I learned what happens when they crawl out of the nest.

The parents call them from a distance

and encourage them to come out.

They know when the babies are ready.

After the babies reach the ground

each one found a tree to climb up, crying for food,

encouraged by their parents.

The parents even use the food

as an inducement to climb higher.

A few of the young I watched

did not manage to climb into a tree the first day

despite the constant importuning of their parents.

These worried me as much as they worried their parents.

They were at great risk on the ground.

But all the baby orioles I watched over 3 years

made it into the trees.

d d

Hero and his Father

For three days, I charted the progress of Hero and his brothers or sisters

into higher and higher branches.

By the second day the birds were flying from twig to adjacent twig

by the third day they were forty feet up in the walnut and sycamore trees

And then into the 80 foot cottonwoods.

The third of fourth day they could fly farther and were all gone.

The same process happened the next year, more of less,

with the Orioles in different trees.

After the third or fourth day their elaborate education begins.

Various bird books say that Orioles tend to nest separately.

But at Hero’s they nest in a colony, with at least 10 pairs---

though this varied over different years.

The birds are probably all related, to some degree.

The bird books also say that in Central and South America

where they over winter, the Orioles tend to travel in groups.

I suspect that these groups are closely related birds

who migrate to the same areas

and return to the same areas the next year.

Orioles can be loosely communal and I suspect

that if I were able to travel with Hero's family to, say, Costa Rica

there is another Hero's Wetland down there,

where the many Orioles of Hero's Wetland stay loosely together.

The fact of this migration and family resilience over

an area of thousands of miles fills me with admiration.

No one knows exactly what the daily life

of an oriole over a years or years is like

and one of the main questions I had watching them for 3 years

was just what they did after they flew

from the high trees surrounding the

nests.

I would occasionally see Orioles in late summer----

young birds with the mother or father, but they are always

on the move, and it is very hard to determine what their lives are like.

Certainly their lives are as complex and interesting

to them as human lives are to humans.

From what I gather from observation, it appears

that the whole summer is spent in wandering

teaching the young birds how to be adults

until migration in the fall.

I have seen one family take care of the

young for more than a month beyond fledging the nest.

Both the male and female attended to the babies,

the babies continuing to ask for food a month after learning to fly

The bird books say that it is the male that cares for them,

but this is not always true.

The family was close in contact, intimate

and stayed within earshot of each other all through July

eating Mulberry berries, bugs,

and sweet water I put out for them.

The three young I watched quickly grew

to be as large as their parents

and looked like their mother.

Hero and His Mother

The Northern Oriole is gold in some lights

hence the Latin or Spanish "oro" or gold.

But in other lights it is yellow, orange or even crimson.

This bird has nothing to do with the blood covered gold rocks

that Europeans coveted to the harm of continents.

It is not gold like the rock of that name

but gold as a sunrise, orange and yellow

like the fruits it loves to eat.

I would rather it were called the Sunrise Bird,

since its black back has white streaks across it

like clouds under the moon

and its breast is brilliant yellow orange

as the sun rising to eclipse the night.

But no matter, Oriole will due.

It is not as badly named as the Monarch butterfly

which has nothing to do with the ego of Kings.

The Oriole is a seeker of luminous fruit

and loves to nuzzle and eat flowers

seeking the nectar of Yellow Buckeyes

and other flowering trees.

Its clear and melodious song at sunrise

echoes a dream of spring orange blossoms

more sweetly yellow than ripe pears

replete with the innocent clarity of spring dawn.

Burnished copper is not as bright

nor is crimson fire in stained glass as luminous

It is more of fire than sun shinning through wine

or orange autumn leaves

caught in the wind and

rising into the red sky at sunrise.

.

Hero the Oriole Grown Up

and Returned to Hero's Wetland

The female is not as brightly colored,

but just as beautiful, with a hints of orange, ochre and purple

like orange grasses in a wheat colored autumn field.

They both are quick witted and very intelligent

and live their lives at a pace that

made me feel clumsy and slow.

The males return to the Wetland before the females

flying thousands of miles.

They sing loud songs of yearning as they wait

for the females to return from the south.

When the females return, the male and females

stay in close touch with each other all day

calling to one another as the busy about eating and

loving and getting ready to nest.

Once they decide where they will nest

the female begins seeking nest material

as the male watches nearby.

She is incredibly thorough about doing this

and inspects anything that might be used as thread.

Her preference at Hero’s Wetland is milkweed fiber,

a plant which not only is a host to orioles

but also to Monarch Butterflies and Milkweed Beetles,

which, like the Monarch and Oriole, are also orange and black.

This plant, the orile and the beetles harmonize with one another

and appear to have evolved together, and like old friends or couples

come to resemble eachother.

It is spring and last years Milkweed stems are still standing and stiff.

She lands on one and dances up the stem like a tight rope walker

and expertly uses her beak to tear open the stem.

I used to make a living weaving and restoring carpets

and her skill and speed with her beak far surpassed

what I could do.

She pulls out a thread, careful not to break it

and then dances further up the stem

pulling at it like a gymnast, until at last

she has a long thread of a foot or more

and she flies off to her nest with it.

Sometimes the thread catches on a branch as she flies

and loathe to let it go,

she holds on and it jerks her back in mid-flight

like Charlie Chaplin being jerked back by his own cane.

When I saw this happen a few times, it was hard not to laugh.

But she is determined, and untangles the thread and brings it to the nest.

She appears to twist or slightly spin the thread

like silk or wool, to make it stronger

as she darns the thread into and out of the growing nest.

She uses her beak like a needle

weaving a satin bed for her babies.

Weaver of Dawn

She works: darning and weaving, going to get more thread

darning and weaving as ths the sun rises

and climbs into the middle of the sky and

then begins to go down.

She stops only occasionally to drink

from the wetland or eat.

For tow or three days she weaves.

The male encourages her and feeds her

as she begins to settle into the finished nest.

I could often hear her respond to his calls with

a delicate voice from inside the nest.

The nest as it grows is like a wedding veil

holding lilac and rosy light, shimmering with the soft

fine-spun fiber as the sun rises.

She weaves her nest of twilight silk

the embroidered beauty of dawn.

Gossamer filaments glisten in the sun

wound around twigs, stitching silver satin

into a shimmering veil,

designed not to keep the world out

or to separate this world from that,

like a forbidding mystagogue,

but rather

and she does it in praise of this world---

the only world there is.

She weaves beautiful threads of the earth itself

into a nest of dreams, to give the earth back to itself

to give new life to life and new being to being.

She does it

for her mate and her babies

and she does it for the joy of doing it.

She weaves herself into the glistening interior

of a nest

made of homespun milkweed

where she will sit for some weeks

until at last she brings new magic

to birth, born into a world of song.

Out of her nest new Sunrise Birds will come

and each of them will flutter down

into a world of wonders

and each will wear the sunrise on their breasts

and she will teach each of them to love life

as much as she has.

Weaver of Dawn

(Close-up)

|